GhostSec, the hacktivist collective targeting ICSs

Introduction

To be able to achieve their objectives, hacktivist groups have been traditionally employing techniques such as distributed denial of services (DDoS), website defacements, and leaks of documents. These operations are usually conducted to advocate for specific social or political causes.

Recently, it has been observed that hacktivist groups have shifted towards the targeting of Industrial Control Systems (ICS). These types of operations are quite effective for creating severe disruptions to industrial facilities and gaining media attention given the nature of the targeted devices.

In particular, GhostSec is a hacktivist group that has been recently making the news for adding a new focus within their catalog of activities claiming to have conducted operations against ICSs. Through their social channels, the group is promoting their operations by sharing pieces of evidences where they claim access to water pump interfaces, GNSS satellite receivers, and other industrial system interfaces.

Examples of GhostSec posts related to operations against satellites receivers and water pump systems

The YCTI Team has been able to retrieve a guide shared by members of the collective in which it is possible to identify tips and tricks on how to exploit exposed operation technologies (OT) devices, such as Supervisory Control And Data Acquisition systems (SCADA) and Programmable Logic Controllers (PLCs). The guide seems authentic, as the content matches the tactics, techniques, and procedures (TTPs) used by the collective for the exploitation of ICS devices.

After giving a brief introduction of the GhostSec collective, this article will provide an overview of the techniques described in the guide; ultimately, evidence from the methods used by the collective to exploit ICS systems will be provided.

The result will show that GhostSec is likely making use of a series of techniques that do not necessarily involve technical exploitation – such as 0-days – against specific ICS devices; on the contrary, many GhostSec operations are carried out by accessing unsecured devices that are openly communicating to the internet, by exploiting default factory credentials or misconfigurations such as lack of authentication.

The GhostSec collective – Origins

The group’s origins date back to 2014 when its goals were different than social or moral hacktivism. GhostSec is an Anonymous collective born as an offshoot of the Ghost Security Group whose original aim consisted in countering websites and accounts related to terrorist organizations and, in particular, ISIS members.[1] Following internal ideological divergences the original group split and formed GhostSec. Allegedly, this group was tasked with OSINT activities and data gathering to be shared with law enforcement agencies in order to thwart terrorist activities. It is not clear whether the original members of the GhostSec collective are still part of the group, however, a recent interview with one of the current alleged leaders, Sebastian Dante Alexander, indicates that the original collective was founded already in 2014, confirming their initial focus on OSINT activities for shutting down terrorists’ promotion and communication channels.

Since 2022, the GhostSec collective has focused on targeting OT devices to advance its objectives launching Anonymous-style campaigns such as #OpRussia, #OpIran, #OpIsrael and #OpColombia.

From March 2022 to June 2023, the YCTI Team identified that the majority of the operations targeting ICS allegedly claimed by the collective have interested devices located in Russia (34%), Israel (28%), and Iran (25%).[2] These numbers reflect the motives pursued by the collective which are strictly connected to the geopolitical landscape, covering topics such as the Russian/Ukrainian conflict, the sympathy towards Palestinians, and the degrading situation of human rights in Iran, especially after the death of the Iranian woman Mahsa Amini.

The YCTI team observed three main types of operations conducted by the collective targeting ICS systems:

- Accessing OTs exposed web interfaces (HMI or GUI) to change parameters and/or dumping and/or deleting files (55%)

- Using Metasploit to send commands to OTs devices and change their parameters (35%).

- Access remote workstations or PLCs users’ interfaces through the VNC protocol (4%)

New Blood Project – The training field for hacktivists

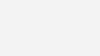

By monitoring the activities of the GhostSec collective, the YCTI Team has identified a platform where followers can learn the basics of operating systems such as Linux, OSINT techniques as well as red team pen-testing techniques.

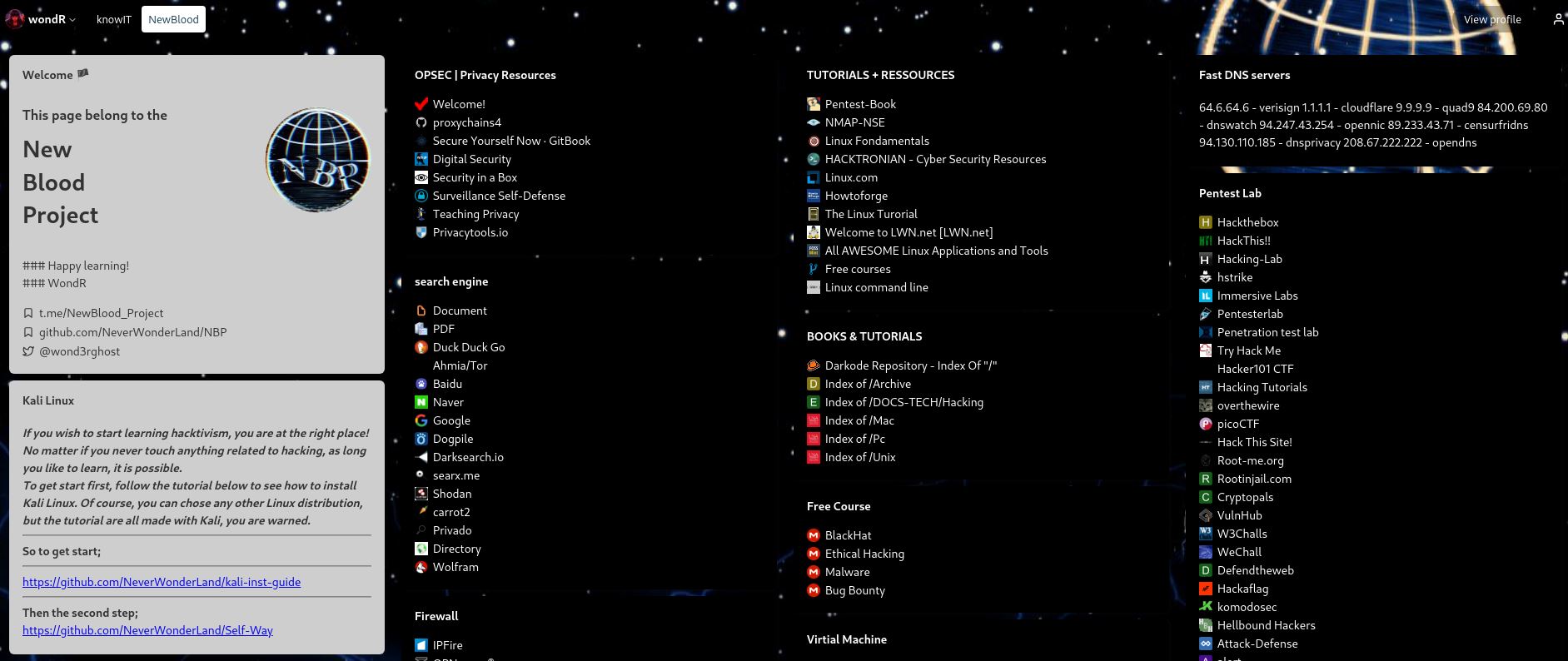

The New Blood Project is a platform available to GhostSec members to learn the basics of hacking.[3] The platform comes as a website page and has a parallel Telegram channel. The project has been created by @wond3rghost (Twitter username) in collaboration with members of the GhostSec community. The promotion of the platform on Ghostsec’s social media accounts started around June 2022.

The Twitter user @wond3rghost is the alias of the GitHub user NeverWonderLand who claims to be the owner of the project.

Evidence of the New Blood Project webpage

Evidence showing the promotion of the New Blood Project in GhostSec channels

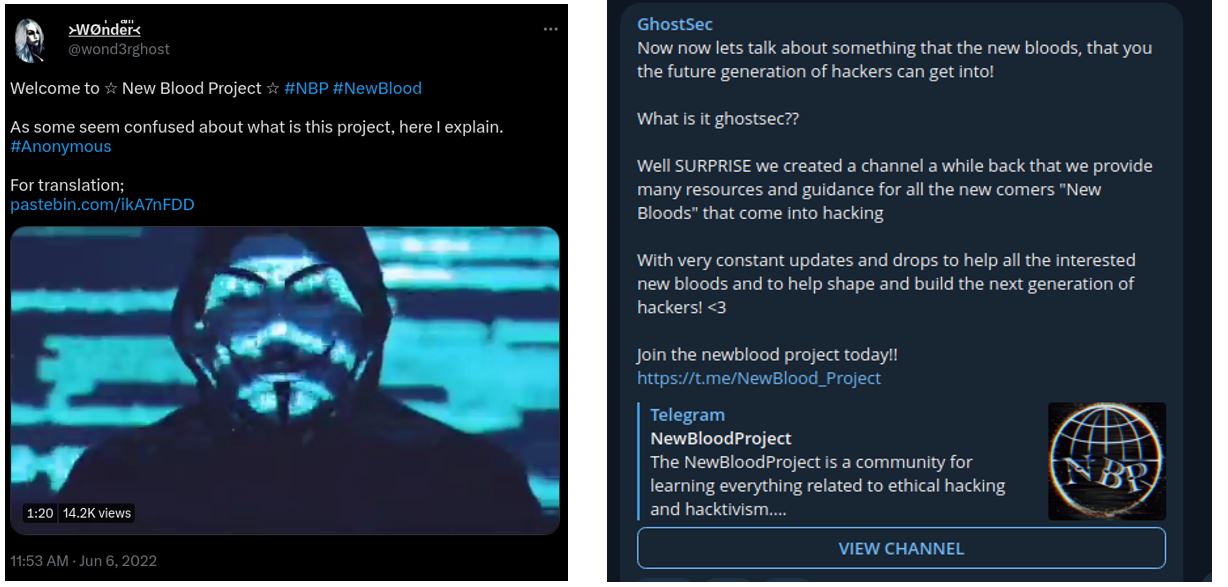

From one of the New Blood Project channels, it has been possible to retrieve a guide shared by members specifically focusing on methods and techniques for exploiting ICS systems.

Tutorial posted in the New Blood Project Telegram channel

The document works as a tutorial to engage the community of hacktivists in targeting industrial control systems through a series of techniques. Following, a brief description of the methods described in the guide will be provided.

Shodan, Modbus scanning, and Metasploit

As set out in the introductory page, the guide will provide methods to enumerate and hack ICS systems. The first section is dedicated to understanding how ICS works in order to understand what type of vulnerabilities can be found with the help of the Shodan search engine.

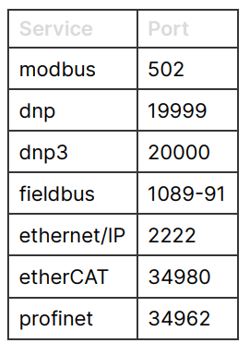

The guide helps the reader identify the vulnerable systems by explaining the dedicated connection protocols used by ICS devices.

List of protocols and related default ports

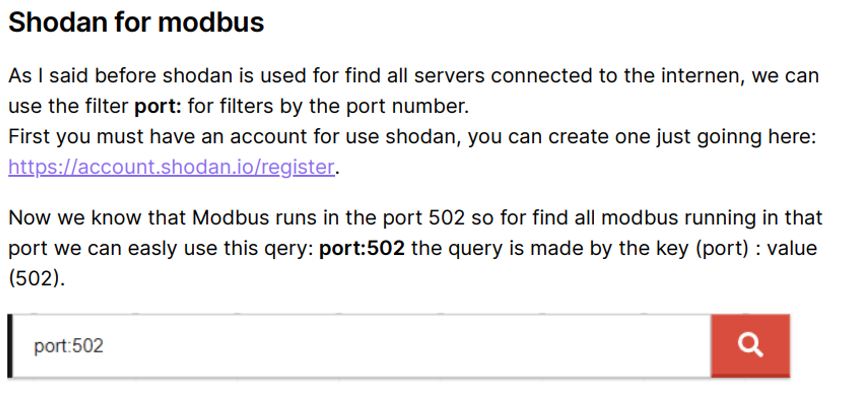

In this case, the author suggests focusing on the devices using the Modbus protocol and gives examples of how to identify the devices and related IPs with Shodan.

Example of a query using Shodan

The guide also shows the fundamentals of the dedicated connection protocols used by ICS and suggests a way to find devices which are specifically using the Modbus protocol.

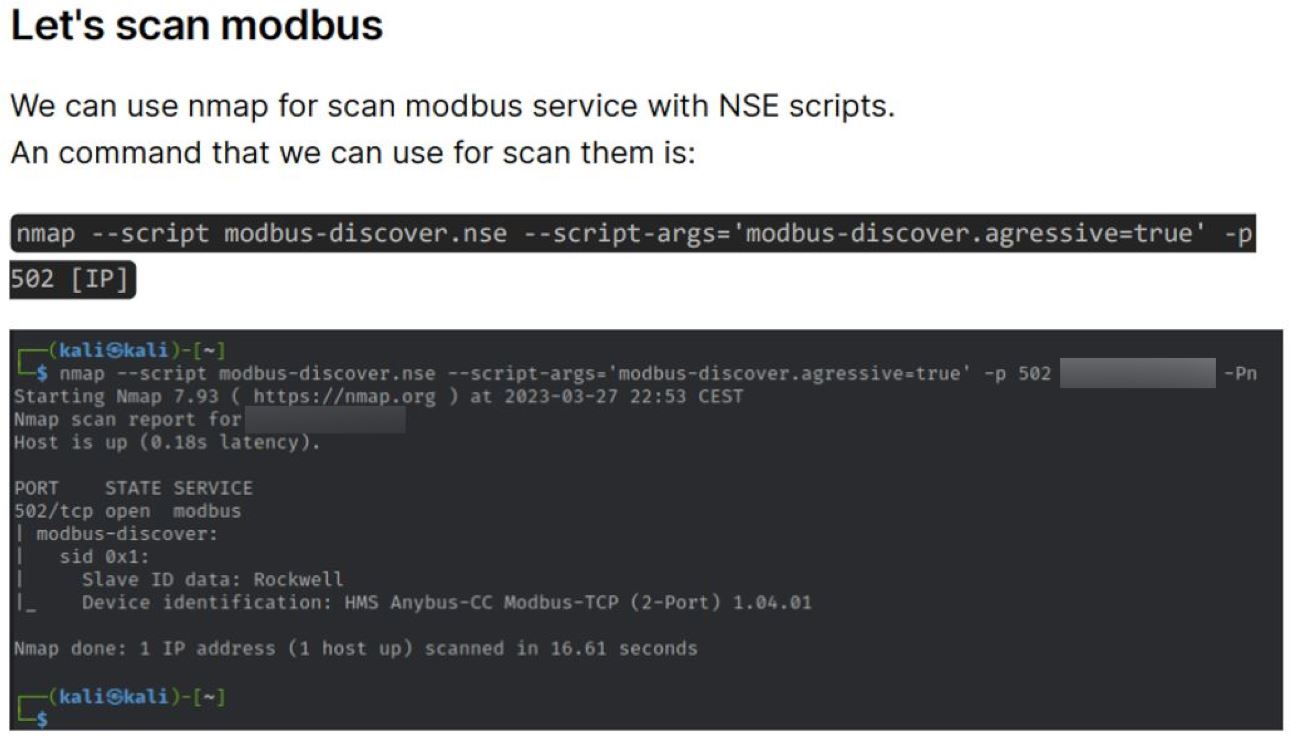

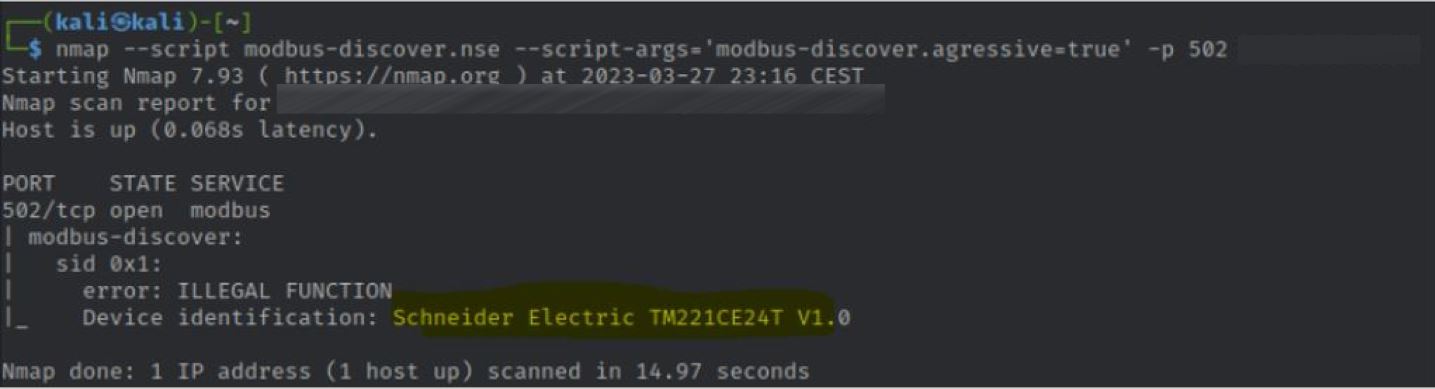

Once the exact devices are identified, the guide shows how to use Nmap to find the specific default open port “502” and the related characteristic of the device such as vendor and model of the PLC.

Scanning procedures with Nmap

The Nmap process is necessary in order to identify specific Schneider Electric Modicon PLCs to change their parameters by sending commands with Metasploit without the need for authentication.

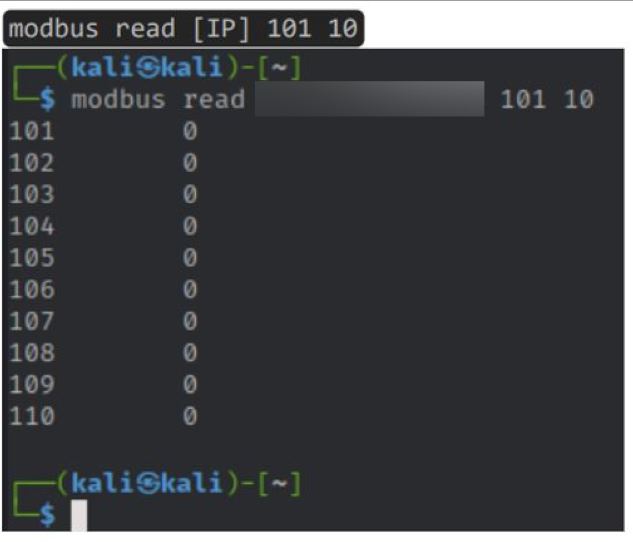

The following are examples of how to use the Modbus-cli to change the coil values in order to set the devices on or off or cause a denial of service status when the device is restarting.

Examples of status values

To sum up, once the exact target is identified, the guide enumerates the options for exploiting the device:

- Denial of Service attack: take down the host

- Default password: log in with default credentials in FTP or HTTP when ports are open

- Using the Modbus-cli: it is possible to send command directly to the device through the Modbus protocol

- Use exploits available for specific PLCs

Port scanning and the VNC method

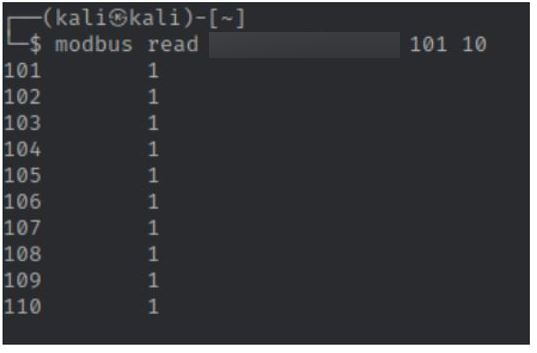

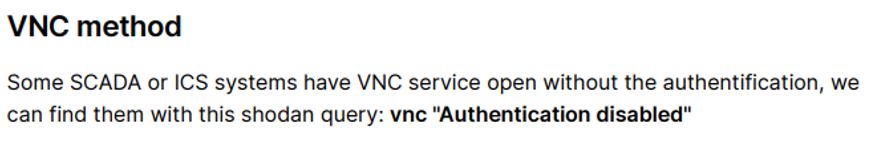

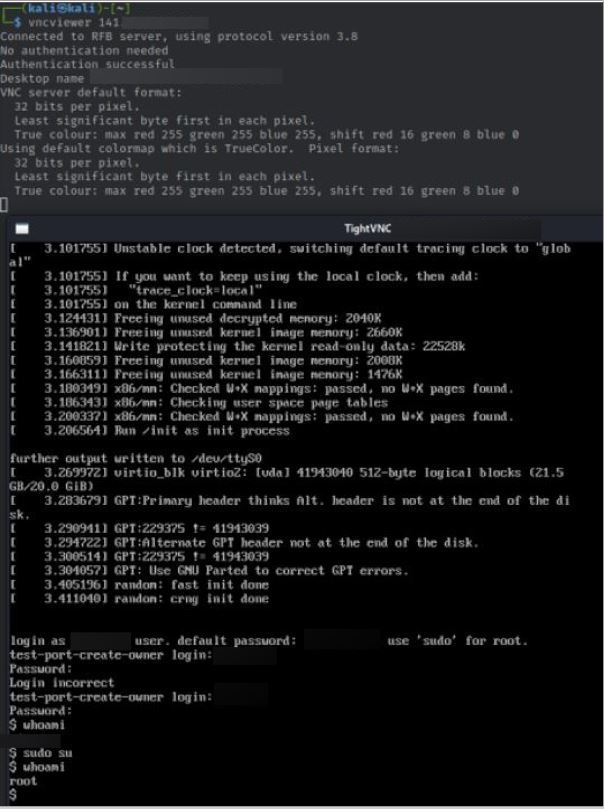

The following method highlighted by the guide is used to find accesses to ICSs via Kali terminal Virtual Network Computing (VNC) addresses. Many OT devices offer the possibility to remotely connect to a web interface to change the parameters of the systems connected to them. This means that the devices are exposed and reachable through the web.

In this case, the author of the guide suggests that it is possible to exploit this exposure by looking for port 5900 which is usually dedicated to the VNC protocol. The following evidence from the guide is related to the VNC method:

The VNC method

In this case, the sample provided shows the panel of a company located in Italy whose port 5900 is open and has been accessed through the Linux command “vncviewer”. The remote connection has been possible as the authentication is set to “disabled”.

Evidence of the VNC connection

A further example shows how to find default login credentials once connected to the remote system via VNC by using a terminal. In this case, the connection may have led directly to a Linux system as the image shows commands in what seems to be a remote shell.

Evidence of a VNC connection to a remote system

Accessing unprotected ICS Systems

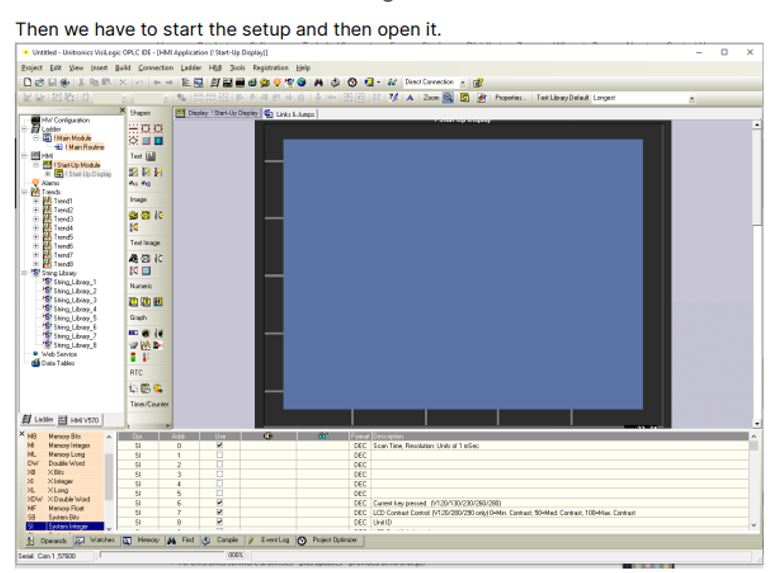

Interestingly, the guide dedicates a section to describe ways to access user interfaces for specific vendors’ devices. As reported in the following evidence, the guide describes how to access the GUI panel of UNITRONICS devices by using a dedicated software called “visilogic”. Once the software is installed and the information related to the UNITRONICS PLC is configured, the software gives access to the dedicated control page of the UNITRONICS device.

Evidence of accessing Unitronics interfaces

In the next sections, the YCTI Team brings examples that are reflecting the techniques described in the guide. These examples consist of incidents claimed by the GhostSec collective and screens are taken from the official channels related to the hacktivist group.

GhostSec #OpRussia and #OpColombia: VNC and default credentials

In the context of the #OpRussia campaign, the GhostSec collective shared evidence about a remote connection to an unsecured device using the VNC protocol. The picture shows the interface seemingly related to a chiller plant showing statistics and temperatures of the connected sensors.

VNC connection to an ICS

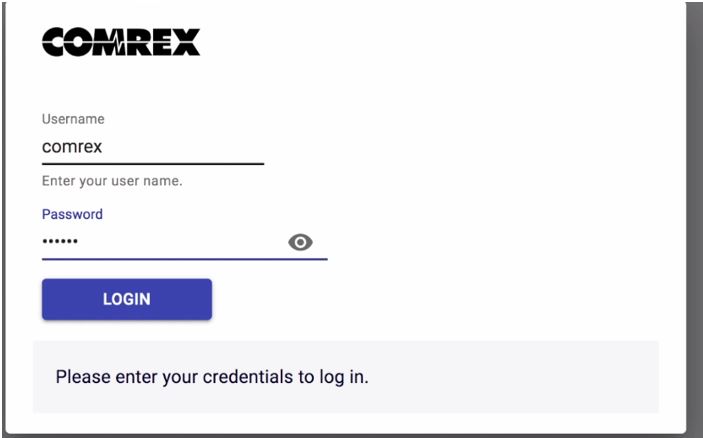

In the recent #OpColombia conducted by SiegedSec in collaboration with GhostSec, the collective claimed to have hacked into radio broadcast devices, showing a video where they access a device related to the COMREX vendor, used for radio transmission.

Evidence from the video posted on the hacktivist channel showing the access to a COMREX device

The access page shows the default username “comrex” and a six-letter obfuscated password. By browsing the vendor’s page, it has been possible to find out that COMREX already alerted users about the risk of using default passwords which, as per the default setting, is set as “comrex”. Curiously, the evidence reported by the collective shows that they access the device using the “comrex” username and a six-letter obfuscated password which coincides with the default password of the device.

This type of information has likely been identified through OSINT as the vendors have already warned through an official alert that many Comrex devices worldwide are using factory credentials and that this information has been shared and circulated in the cyber underground.

Evidence of the vendor alert on the website warning about the use of default credentials

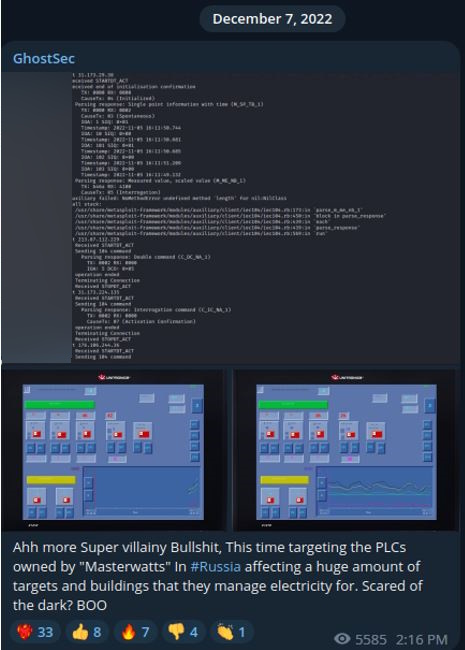

Ghostsec #OpRussia: Accessing Unitronics Devices

In one post, GhostSec shared pictures and announced the targeting of a PLC located in Russia.

The operation claimed by Ghostsec where Unitronics interfaces are visible

The evidence shows the brand of the vendor and the specific version of the compromised device. In this instance, it is possible that the collective typed specific queries in Shodan using the name of the country and the UNITRONICS name to find the related IPs linked to the devices.

From the evidence provided, it is difficult to ascertain how exactly the collective has been able to access the interface of the Unitronics device by using the “visilogic” software or by simply accessing it through a web-based interface with weak or no authentication.

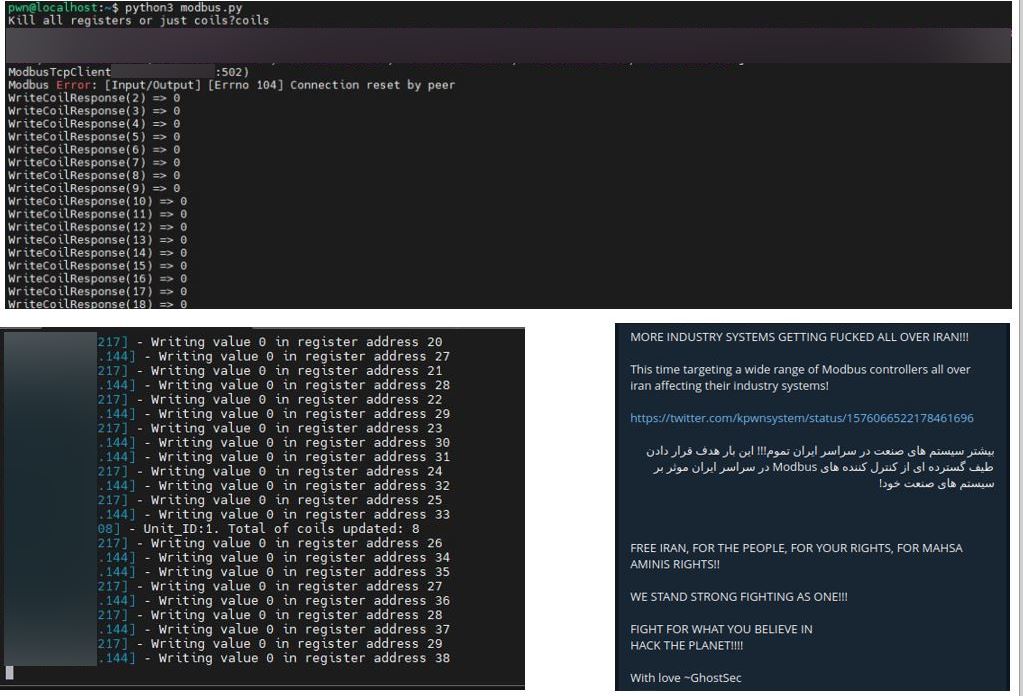

GhostSec #OpIran: Exploiting ICS using Modbus

In many cases, GhostSec has been using Metasploit and custom scripts to change the parameters of targeted devices.

Evidence of parameters modification of devices using the Modbus protocol

Evidence of parameters modification of devices using the Modbus protocol

As shown in the guide, the Modbus protocol can be exploited to send commands to ICSs without the need for authentication, thus allowing to stop CPUs – i.e. stop-cpu modicon framework for specific brands of PLCs – and or changing the parameters of the registry of PLCs.

Shodan is of course pivotal to find the list of PLCs and related IPs exposing port 502.

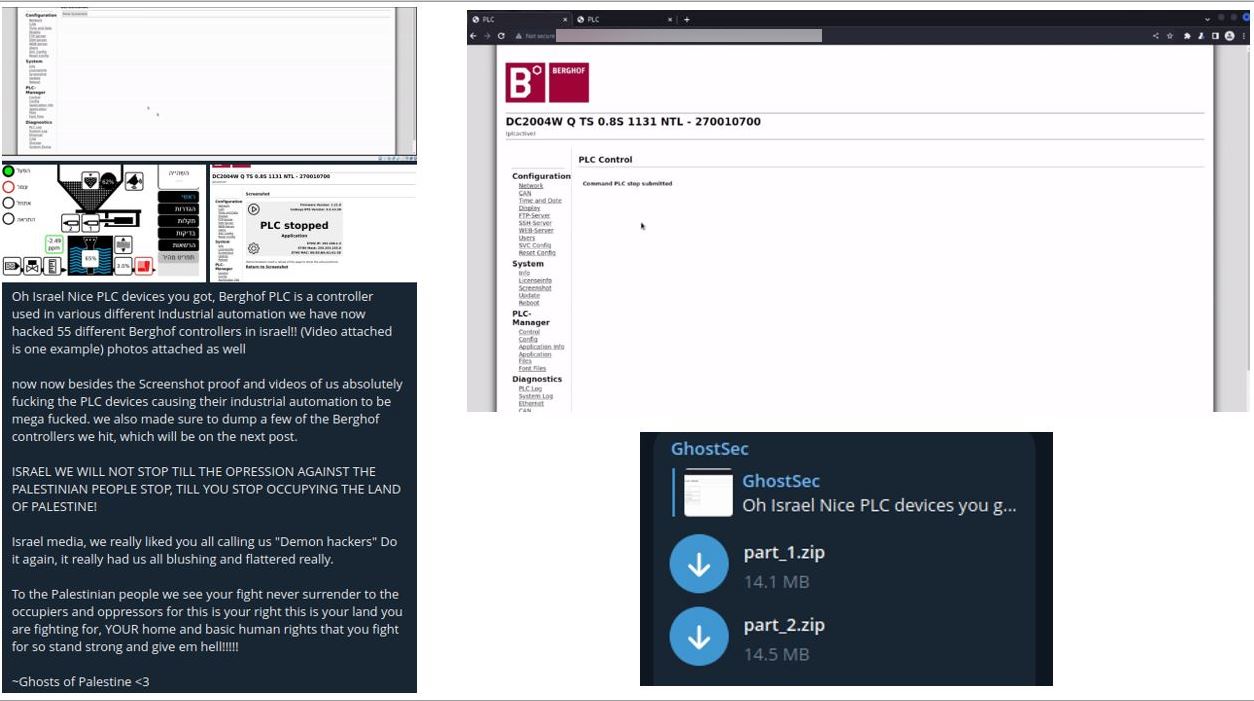

GhostSec #OpIsrael: Using zero-day against ICSs?

One of the most famous operations claimed by the GhostSec collective dates back to September 2022. The group announced the successful exploitation of a large number of Berghof PLC devices geolocated in Israel. As usual, the group provided information about unauthorized access to the interfaces. This time the collective also shared two archives of data dump likely retrieved using the backup functionality of the Berghof admin panel.

Evidence showing the announcement, the proof of access to the admin interface, and the data dump archives

Researchers have been confident by affirming that the PLCs and the admin interface might have been accessed through a combination of Shodan-dorking and brute-forcing default or weak credentials. At the time, both the PLC administrative panels were reachable through the web allowing in-depth analysis over the specific incident.

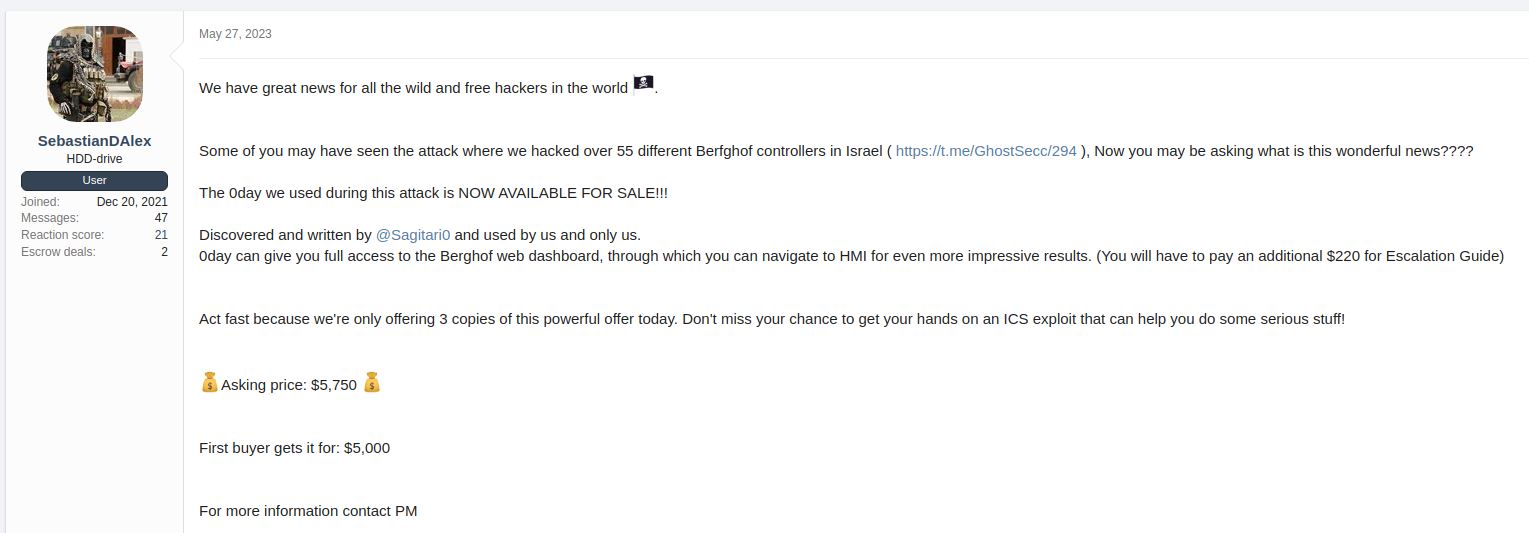

However, months later, on May 27, 2023, one of the leaders of GhostSec SebastianDAlex posted a thread on a notorious underground forum advertising the selling of a zero-day vulnerability affecting Berghof devices claiming that this was the same zero-day used to exploit Berghof PLCs in their attack back in September 2022.

Evidence of the 0-day post was identified on a notorious underground forum

Although it is not possible to ascertain whether the selling results legit nor whether a 0day has been used to gain access to the admin panel of the Berghof PLCs, the user is still active on the forum and it has not been banned. Further posts in the thread show that the exploit has been already sold twice.

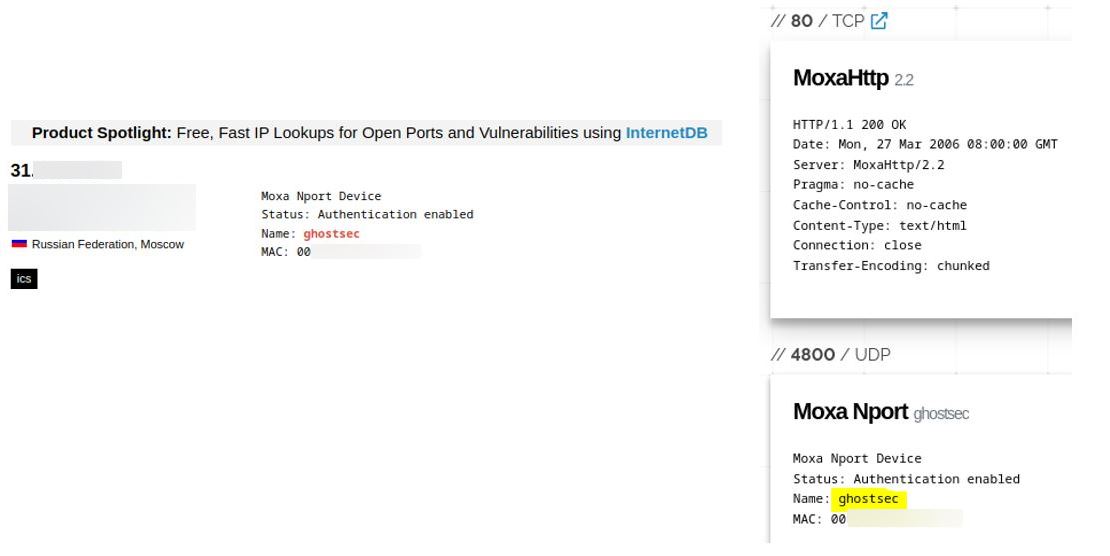

GhostSec – Gaining persistence

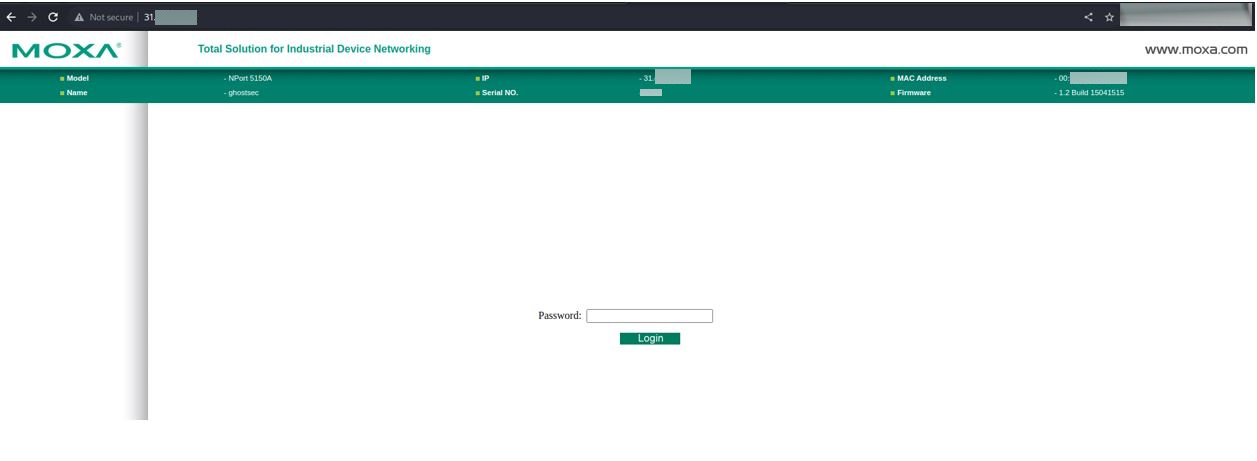

Further research by the YCTI team highlighted the possibility that the collective, once accessed through default credentials or unauthenticated protocols, creates accounts to lock out other users and have free access to the device. The following sample shows a MOXA device displaying the username “ghostsec”.

Username “ghostsec” exposed on a Moxa device

By browsing the web page (without logging in) a MOXA interface is displayed where it is possible to see the existence of an account named “ghostsec”. The IP related to the device is geolocated in Russia. Therefore, this operation might be related to the #OpRussia campaign.

Moxa web interface

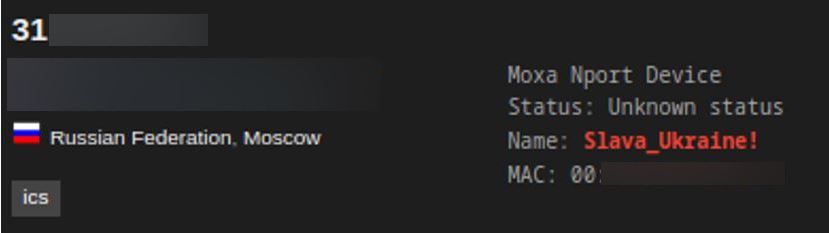

By monitoring the same IP related to the same device, it has been noted that the name of the account has changed over time. In the example below, the same device displays the slogan “Slava_Ukraine!”. Although it is difficult to ascertain whether GhostSec is behind this specific operation, it has been noted that, on top of changing the parameters of a device, hacktivists usually leave a sign of their actions by adding their name or affiliation within the device parameters. This signature process also helps them to gain notoriety and it is useful when the collectives share evidence of their operations across their channels.

Evidence of the username change

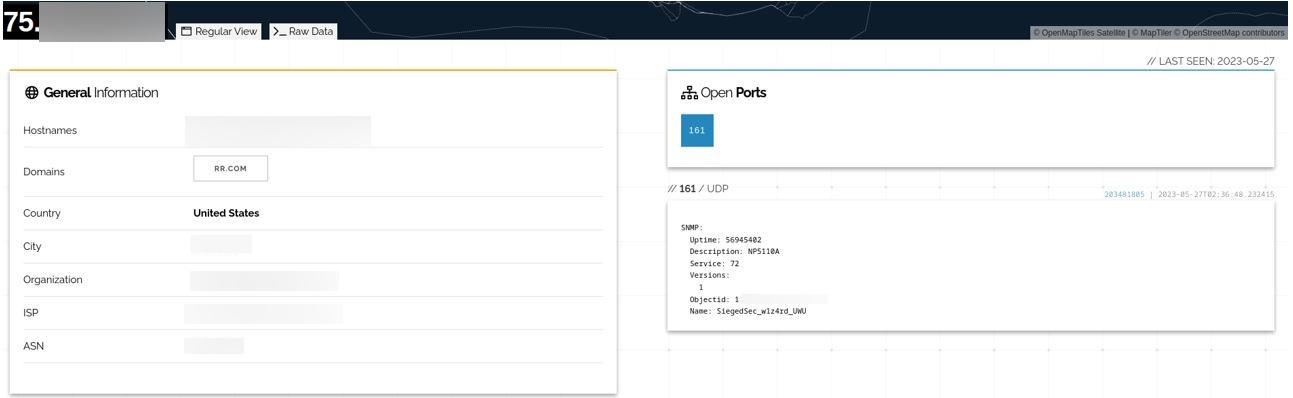

Using Shodan, the YCTI Team found more evidence related to the use of the persistence technique. In the following screenshot, the open port 161 of a specific IP displays the name SiegedSec_w1z4rd_UWU.

Hactivist’s signature evidence

The name refers to a well-known threat actor called SiegedSec which has recently restarted its activities and has conducted operations in collaboration with the GhostSec collective. UWU is the avatar and avatar used by SiegedSec and works also as alias to refer to other SiegedSec members. The word w1z4rd might represent the name of the user who managed to create the account within the compromised device.

According to the info displayed by Shodan, the user has created the account on a device, whose model name is NP5510A. The serial refers to a specific model of MOXA Nport, a device that has been regularly targeted by Ghostsec, which makes use of the Simple Network Managing Protocol (SNMP). According to the user manual, the SNMP protocol can be used to monitor all the connected devices and define triggers for sending specific alarms when, for instance, a password change is detected. Therefore, by having access to this device, not only could the collective have a vision of all the devices connected to it, but also they could have potentially voluntarily triggered the aforementioned alarms.

Is GhostSec bluffing?

In some circumstances, the claims reported by the collective have been supported by poor or, no proof regarding the alleged exploitations. Therefore, it makes it difficult to establish whether all the operations conducted by GhostSec are legit.

The following evidence is one example of a possible bluff that could have been used by the collective to garner attention.

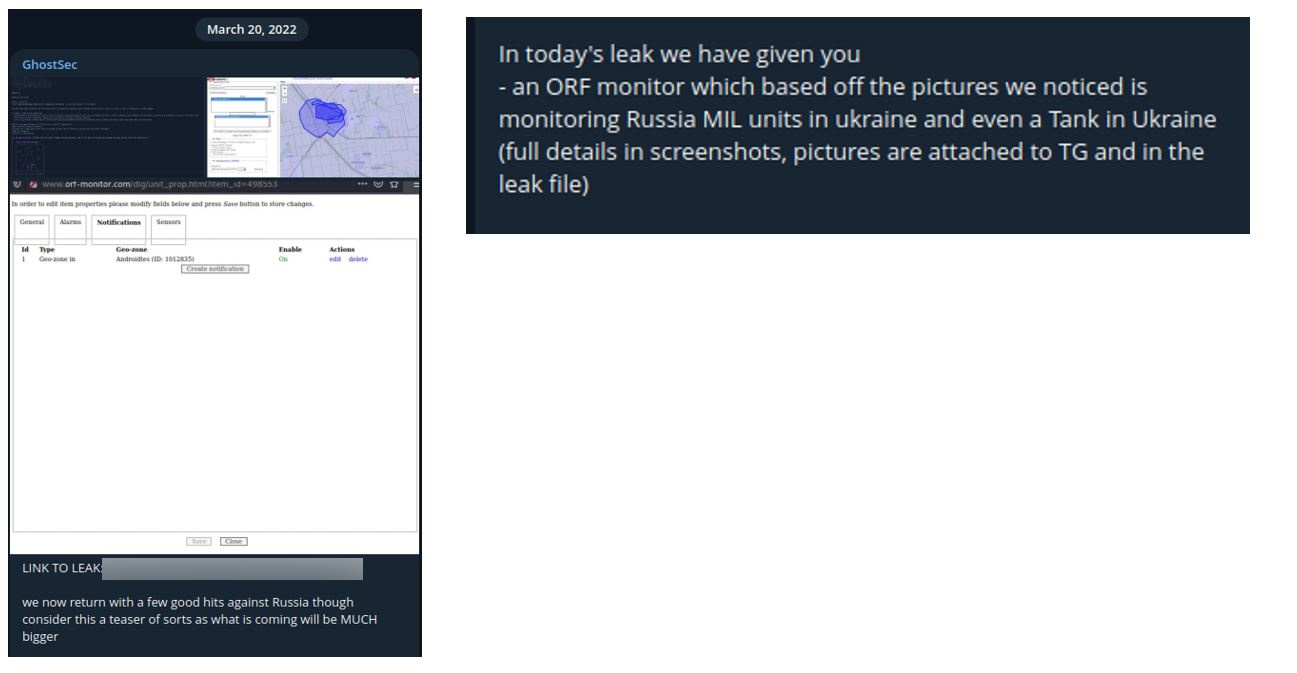

In March 2022, GhostSec claimed to have accessed a vehicle monitoring service and dumped information about vehicle statistics – a Russian military tank – visible from the service interface.

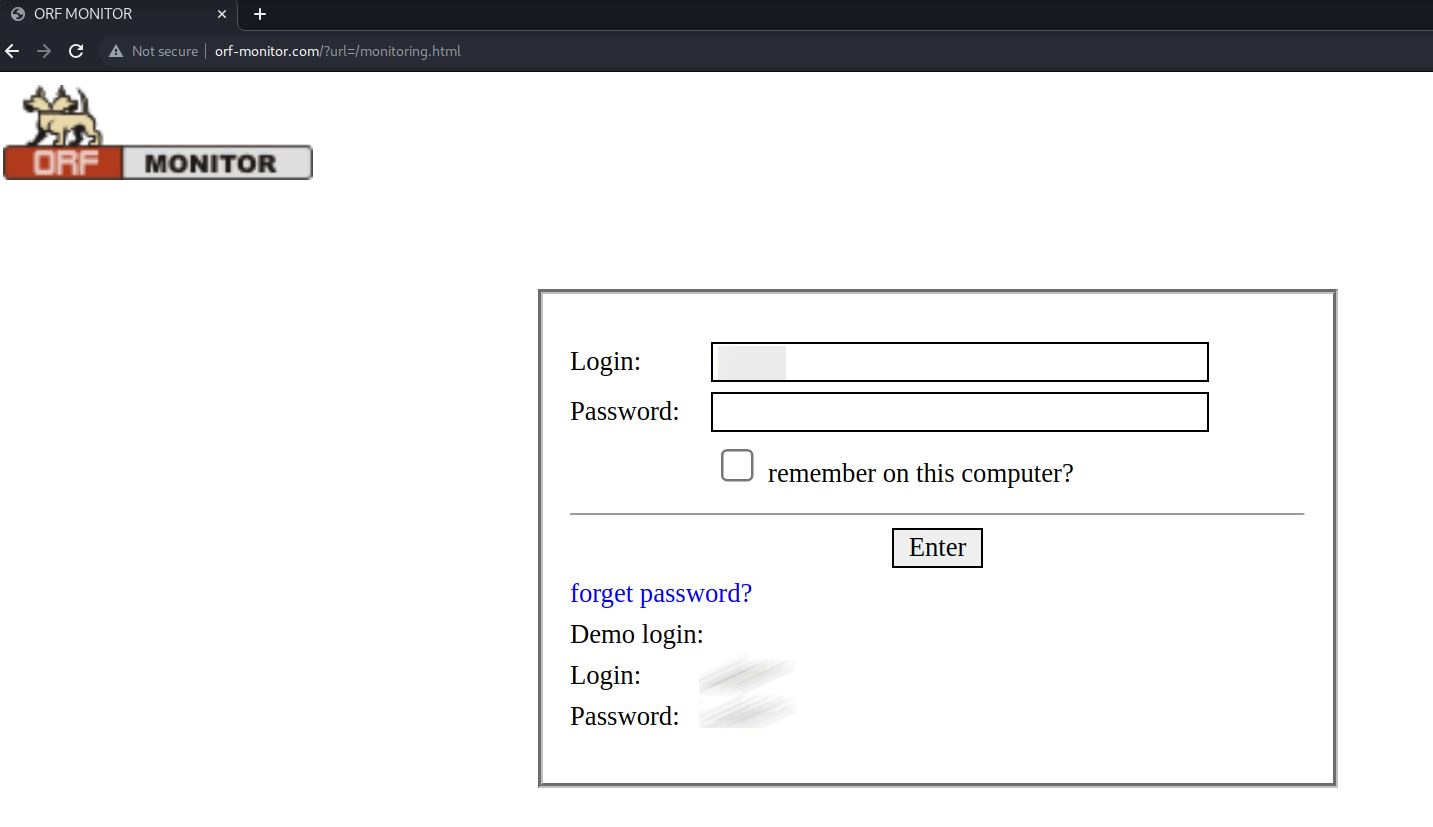

GhostSec post claiming access to an ORF monitoring service

Further research of the YCTI Team highlighted that the monitoring service is accessible through the web and it is possible to log in to what seems to be a demo. The credentials are displayed in plain sight to allow users to have access to the demo service.

Evidence of the demo login webpage of the ORF-Monitor service

Once logged in, it is possible to retrieve the same information dumped by the collective back in March 2022.

Therefore, in this case, it is possible to assume that the collective has used the demo service to gather the information shared in their channel. In this way, they have been able to magnify their operation and, at the same time, they managed to gather attention around their actions by dumping fake sensitive information leveraging the Ukrainian-Russian conflict topic.

Conclusions

Targeting ICSs can lead to severe disruptions and consequences depending on the criticality of the systems connected to them. The fact that devices such as PLCs are exposed to allow operators to remotely access them increases the risks of threats and unauthorized access due to possible misconfigurations.

GhostSec is just an example of hacktivists that uses methods and techniques to find and exploit exposed services. Although it is difficult to ascertain the legitimacy of all the claims made by GhostSec, it is necessary to assess their operations on a case-by-case basis. This is important for at least two reasons: the first is that the constant monitoring allows understanding of the evolution of targets, methods, and new trends used by hacktivists; the second reason is that it allows assessing the real capacity by discerning critical threats from those of lesser importance.

The analysis of the guide containing the tutorials shows that the techniques used to exploit ICSs are more related to OSINT research and the use of publicly available tools leveraging misconfiguration of the targeted devices than the use or discovery of technical vulnerabilities such as 0-days. However, threats related to ICSs devices must not be underestimated as the interest demonstrated by this collective and their ability to exploit them can significantly evolve over time.

References:

[1] https://ghostsecuritygroup.com/

[2] The analysis is based on the claims identified in the official channels of the GhostSec collective. It is worth noticing that some of the claims cannot be validated due to the lack of proof available.

[3] https://start.me/p/MEDrOn/newblood

Author:

Samuele De Tomas Colatin is a member of the Yarix Cyber Threat Intelligence Team. Previously, he worked as a researcher at the NATO Cooperative Cyber Defence Centre in Tallinn, Estonia. He is currently trying to find a balance between updating MISP and living his private life. Spoiler: he has not succeeded yet.